I was once a staunch believer in the power of a hashtag.

Give someone the internet, and you’re giving them a kind of voice no amount of vocal cords can produce. One that has the ability to reach masses. One that can unite a community of voices to form a choir of empowered subjects.

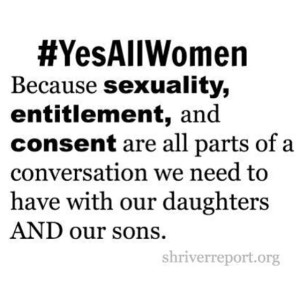

There’s little wonder why #yesallwomen nearly broke the internet this week. Because collectively, women have had enough. Yes. All women. Every last one.

And so, women flocked to social media and created one unified, empowered chorus. Hitting back at misogynistic ramblings and sexist musings.

And for a fleeting moment, it seemed progress was possible. That a hashtag carried weight.

Image via Wendy Sachs

Image via Wendy Sachs

Until #notallmen was started. And many sought to dismantle the conversation.

The fact that #notallmen completely and embarrassingly missed the mark isn’t even the most tragic point here.

The tragedy lies in the fact we are putting all our energy into raising awareness of pressing issues over Twitter, set to achieve what exactly?

Empowerment? Maybe. Awareness? Probably.

But despite all our efforts to fight against sexism, #yesallwomen was still met with resistance. We were forced to recognise that a hashtag carries little power, unable to open the narrow mindsets of the dogged misogynists.

Because many still didn’t understand the cause.

And so, we learnt a lot this week from #notallmen.

We learnt that a hashtag doesn’t educate.

We learnt that a hashtag doesn’t eradicate ignorance.

And we learnt that a hashtag won’t change years of oppression.

Years of enduring men, like that of the ill-fated Elliot Rodger, who believe that women owe them something.

We learnt to effectively fight these #notallmen attitudes, we can’t put every ounce of our time, energy and faith into social media. Global conversations can only get us so far. Awareness can only get us so far.

Clementine Ford, writer for Daily Life, wrote on her blog:

“I am afraid of you, the man who refuses to listen to the experience of women, instead arguing that ‘not all men’ are like that… You are pretending that the frustration of being treated with caution is equal to the frustration of having to be cautious.”

And she’s right. #notallmen are the ones we should be afraid of. The ones who won’t be divorced from their ignorance after reading a single tweet.

Because a hashtag isn’t education. Education is education. And that will always have a bigger impact.

Why is everything on twitter these days about men being rapists and sexual pigs… #NotAllMen

— Hunter (@NunterHormand) May 29, 2014

#Notallmen understand that it’s not all about them.

— Clementine Ford (@clementine_ford) May 26, 2014